During our daily woods walk I spied a piece of birch bark rolled up and lying on the snow. Nibbles also saw it and tentatively stretched his nose toward it for a sniff. I felt myself experience a small hit of adrenalin that often accompanies events that scare or startle me. Other than it being the same size and dimensions of a belly-up grey squirrel, and the brownish-orange colorations on the bark being sort of the same color as blood, it was most definitely a piece of birch bark. Nibbles hesitation to approach it registered in my mind and contributed to my response.

I am not afraid of squirrels, dead or alive, but the “yuck a dead thing” reaction happens regardless of how squeamish something might make me. It wasn’t that I thought it was a dead squirrel, I felt it was a dead squirrel, and there’s a difference. Had it been a dead squirrel I might have had cause for concern. Any animal that might have killed it should have eaten it or moved it off the trail. I would have to decide whether or not to let the dogs think it was Christmas. Did it die from a disease? But I didn’t have to entertain any of those questions because it was clearly a piece of birch bark.

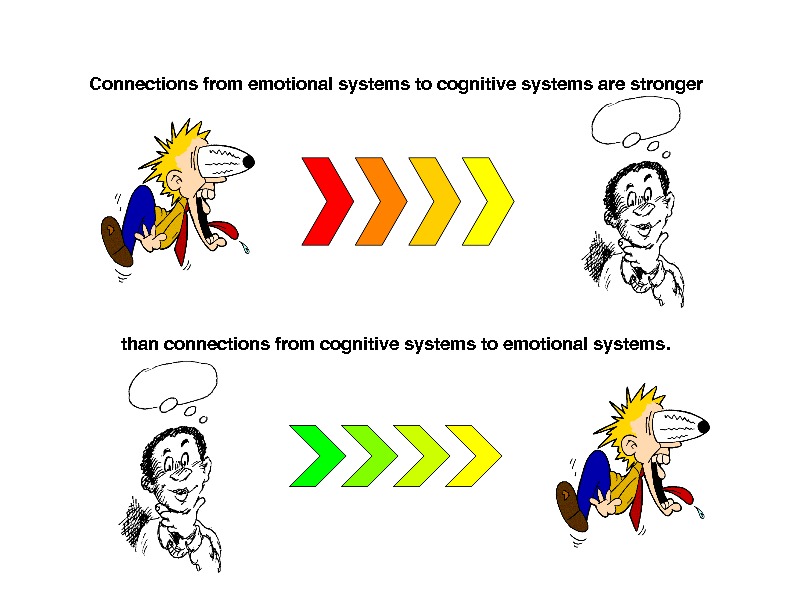

Our brains, and our dogs’ brains, are set up so that information processed by the limbic system, the part of the brain that contains the amygdala, travels faster to the parts of our brain that think and ponder information, than happens in reverse. Had it been a dead squirrel, or something potentially dangerous to me, I was primed to react, even if that only means I would have jumped back and screamed.

How scary or upsetting something might be to us will impact the degree to which we have an emotional response. That emotional response will cause a physical response. Bodies respond to fear in different ways, they freeze, they flee or they fight. With training we get better at responding more thoughtfully when we are afraid, but it’s not easy and takes practice. Even professional actors can experience debilitating stage fright.

When a dog is repeatedly scared by the same thing, and is not given the opportunity, usually through systematic desensitization and counter conditioning, to learn to think about it differently, they are likely to continue to feel the same way about it. It’s the feeling that is going to drive the behavior that you see. When we talk about thresholds to triggers we are referring to the level of concern that allows, or doesn’t, a dog to think about what it is they are dealing with. It is up to us to determine the conditions under which our dogs are more likely to learn new responses. Wanting your dog’s response to change is not enough.